Charlemagne

Denmark’s left defied the consensus on migration. Has it worked?

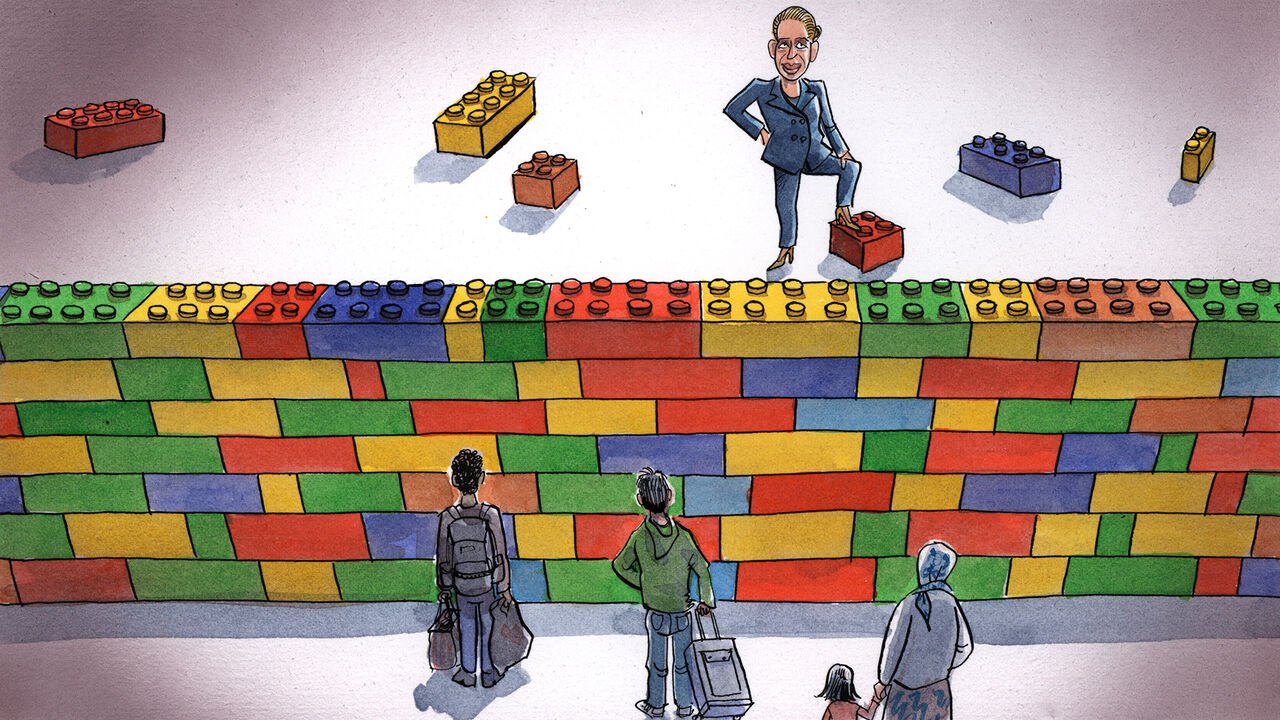

Building walls, one brick at a time

Jul 10, 2025 03:12 PM

VENTURING BEYOND the ring road of just about any western European capital, far from its museums and ministries, often means encountering a landscape that mainstream politicians prefer to gloss over. Many suburbs are havens of familial peace. But others are the opposite: run-down dumping grounds into which societies shunt the immigrants whom they have failed to integrate. In the unloveliest banlieues surrounding Paris, Berlin or Brussels, criminality—whether petty, organised or drug-related—is often rife. Social indicators on education or employment are among the nation’s worst. Ambitious youngsters looking to “get out” know better than to put their real home address on their CVs.

These are uncomfortable facts, so much so that to point them out is to invite the disgust of European polite society. Whether in France, Germany, Italy or Sweden, parties of the hard right have surged as they—and often only they, alas—persuaded voters that they grasped the costs of mass migration. But the National Rally of Marine Le Pen in France and Giorgia Meloni’s post-fascist Brothers of Italy have an unexpected ally: Denmark’s Social Democrats, led by the prime minister, Mette Frederiksen. The very same party that helped shape the Scandinavian kingdom’s cradle-to-grave welfare system has for the past decade copy-pasted the ideas of populists at the other end of the political spectrum. Denmark is a generally well-run place, its social and economic policies often held up for other Europeans to emulate. Will harsh migration rhetoric be the next “Danish model” to go continental?

Ms Frederiksen, who served as party leader for four years before becoming prime minister in 2019, did not pioneer the migrant-bashing turn. Like most western European countries, Denmark had welcomed foreign workers and some refugees from the 1960s on. The tone shifted as early as the early noughties, even more so after an influx of Syrian asylum-seekers reached Europe in 2015. While Germany showed its kind side—the then chancellor, Angela Merkel, asserted with more hope than evidence that “we can manage this”—Denmark fretted that a far smaller number of arrivals might undermine its prized social arrangements.

The Danish left’s case for toughness is that migration’s costs fall overwhelmingly on the poor. Yes, having Turks, Poles or Syrians settle outside Copenhagen is great for the well-off, who need nannies and plumbers, and for businesses seeking cheap labour. But what about lower-class Danes in distant suburbs whose children must study alongside new arrivals who don’t speak the language, or whose cultures’ religious and gender norms seem backward in Denmark? Adding too many newcomers, the argument goes—especially those with “different values”, code for Muslims—challenges the cohesion that underpins the welfare state.

For a place with a cuddly reputation, Denmark has been cruel to its migrants. Authorities in 2015 threatened to seize asylum-seekers’ assets, including family jewels, to help pay for their support. Benefits were cut, as was the prospect of recent arrivals bringing in family members. Being granted permanent residency, let alone Danish nationality, takes longer than almost anywhere else. And it is far from guaranteed: those offered refuge are afforded protection only as long as conflict in their home country rages, their status reviewed every year in some cases. Somalis and Syrians once settled in Denmark are among those who have been asked to head back to a “home” their children have never known.

In 2021 it was proposed that newcomers seeking asylum in Denmark should be processed in Rwanda instead, a plan that fizzled. A law passed by Ms Frederiksen’s predecessor, but which she enthusiastically carried forward, cracks down on “ghettos”, now known as “parallel societies”: estates housing lots of folks with “non-Western backgrounds”. If crime, unemployment or other metrics are too high, failure to reduce them (or the “non-Western” resident share) can result in their being razed or sold off.

The upshot of the left’s hardline turn on migration has been to neutralise the hard right. Once all but extinct, it is still only fifth in the polls these days, far from its scores in the rest of Europe. For good reason, some might argue: why should voters plump for xenophobes when centrists will deliver much the same policies without the stigma? Either way, that has allowed Ms Frederiksen to deliver lots of progressive policies, such as earlier retirement for blue-collar workers, as well as unflinching support for Ukraine. The 47-year-old is one of few social-democratic leaders left in office in Europe, and is expected to continue past elections next year. Before that, she has a megaphone to pitch her unyielding approach to migration to the rest of the EU: Denmark holds the bloc’s rotating presidency until the end of the year.

To tolerate or not to tolerate

Denmark’s near-consensual diagnosis that the poor are left to pick up the pieces of botched migration policies is worth pondering. But this recent visitor to Copenhagen left with an uneasy feeling. Immigrants and their descendants make up about 1m of Denmark’s 6m-strong population. The ugly upshot around limiting immigration—however noble the motives—is that it seems acceptable to be nastyabout immigrants. As a class they are spoken of as a “threat”, an inconvenience to be dealt with. Disdain for Muslims seems tacitly endorsed by officialdom, as if each were a potential rapist or benefits cheat. Refugees with proven fears of persecution are expected to learn Denmark’s language and adopt its customs—but face being kicked out at any minute. Such an us-versus-them approach is corrosive to a country’s sense of citizenship. How can people embrace a society that holds them in contempt? Denmark may have done a better job than others of grasping that migration comes with costs. But it risks shattering the social cohesion it is trying to preserve. ■