Cheap workers

British labour is a bargain

Thank Brexit and stagnant wages

Jul 12, 2025 01:24 PM

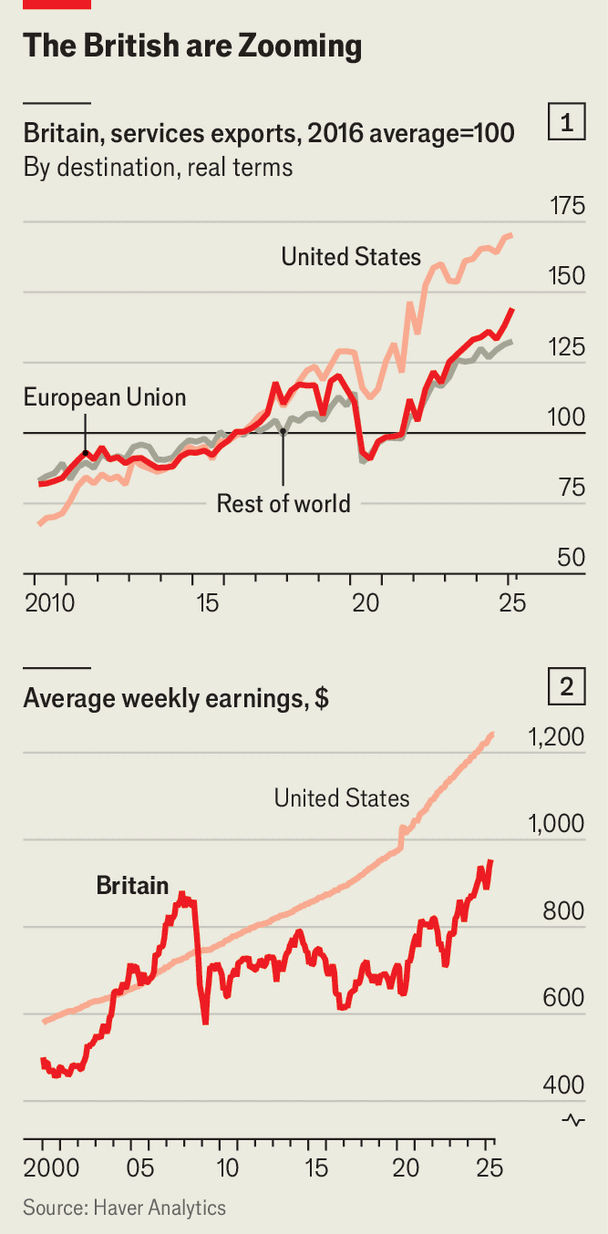

SUCCESS STORIES in the British economy have been rare of late. But there is one notable exception: the boom in selling services abroad. Over the past decade, Britain’s services exports have grown by around 45% in inflation-adjusted terms, even as the wider economy grew by only 11%. America has been a particularly good customer. British services-export volumes across the Atlantic are up by 70% compared with 2016 (see chart 1).

Several things have fuelled this rise, some old, some new. Britain has always benefited from a well-educated and English-speaking workforce that sits in a favourable timezone for working with both Asia and the Americas. A specialisation in easily traded professional services proved to be a boon as work moved online following the covid-19 pandemic.

Most important of all, Britain is cheap. Real wages fell for years after the financial crisis and have been slow to recover. Sterling took a beating after the Brexit referendum. That adds up to an appealing proposition for would-be foreign outsourcers. As recently as 2014, average weekly earnings in Britain were near-equivalent in US dollar terms to those in America. Today American wages are 30% higher (see chart 2).

Firms have noticed. JPMorgan Chase, a bank, moved some of its digital operations to a big new office building in Glasgow last year. Mark Napier, its Glasgow head, lays out the economic case. In terms of salaries Glasgow-based coders sit mid-way between the bank’s lower-cost American outposts (Texas, not California) and its operations in India—but if anything, slightly closer to India. Over the years, that comparison has moved in Glasgow’s favour. A coder in India once cost about a quarter of a Glaswegian equivalent; now it’s over half. About a third of JPMorgan’s Glasgow-based work is now for its American division. Goldman Sachs, another bank, set up stall in Birmingham in 2021 after commissioning a search across Europe for a mid-priced city with a deep talent pool.

Alexander Mann Solutions (AMS), a British recruitment firm, runs part of its American operation from Belfast. The five-hour time difference with the East Coast is a little inconvenient, but labour is almost 40% cheaper than in America, says Nicola Hancock from AMS. The firm does have to brief its offshore recruiters that British vagueness doesn’t always land well across the Atlantic, where business culture is more literal and to-the-point, she adds. Americans also do not always know what “half past one” means.

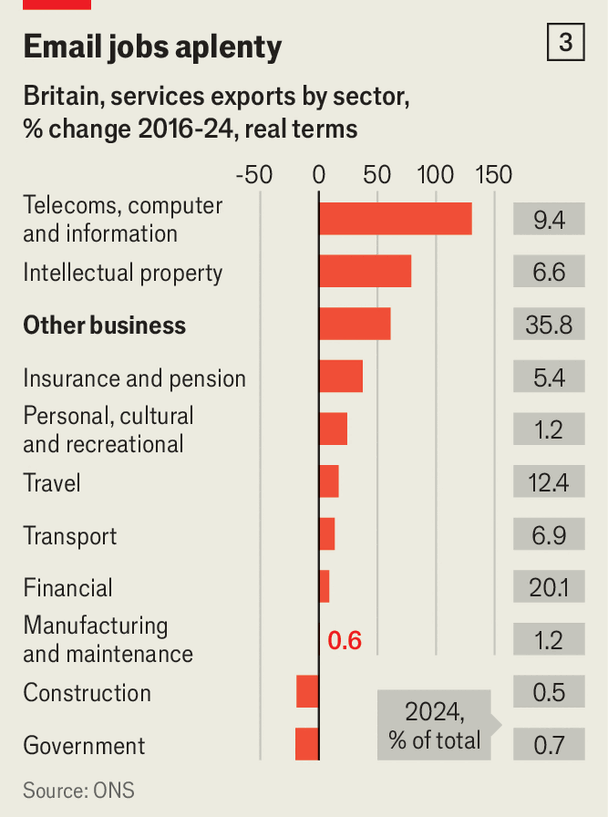

Britain’s particular strength lies in the vaguely named category “other business services”, encompassing consultants, lawyers, public-relations types, accountants and more—what the post-covid generation might call “email jobs” (see chart 3). Along with finance and insurance, these account for two-thirds of the rise in Britain’s services exports since the Brexit referendum. The split with the EU, paradoxically, encouraged the services boom by crushing sterling, making British salaries cheaper for foreigners. Goods exports, which are more directly affected by post-Brexit trade barriers, are over 10% lower in real terms over the same period.

Although those sectors have tended to be concentrated in London, which supplies just under half of Britain’s services exports, the cheap-but-qualified labour proposition is often strongest in Britain’s second cities, such as Birmingham and Glasgow. The expansion of higher education in the 1990s and 2000s pushed up the number of university graduates around the country, but jobs for them did not always follow.

Research by Anna Stansbury of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and co-authors has found that the graduate wage premium—the extra amount a degree-holder can expect to earn, controlling for demography—has dropped in every region of the country bar London. That leaves a pool of cheap talent for multinationals such as Goldman Sachs to scoop up. Not quite the muscle-bound factory workers that some advocates for “levelling up”, the project of rebalancing the economy away from London, typically like to talk about, but a success story nonetheless.

Britain’s success in providing professional services on the cheap has so far mostly gone unnoticed. One exception is the film business, where Britain’s cheap and high-quality labour (plus a sprinkling of subsidies) have lured big-budget productions such as the latest entries in the “Mission: Impossible” franchise. Hollywood’s complaints to Donald Trump prompted a brief flirtation with movie tariffs, though the president now seems to have dropped the idea.

Tariffs, then, are unlikely to disrupt much. A more plausible candidate for concern from Britain’s perspective is artificial intelligence. Mid-wage “email jobs” are prime candidates for automation, if AI models become more reliable and manage to crack the sort of multi-day and multi-week tasks that professional workers spend most of their time on. But for now, any sort of economic win is welcome news of the sort Britain desperately needs.■