A CEO’s summer guide to protecting profits

Deconstructed

It is beset by fragmentation, overregulation and underinvestment

Jul 11, 2025 05:35 PM

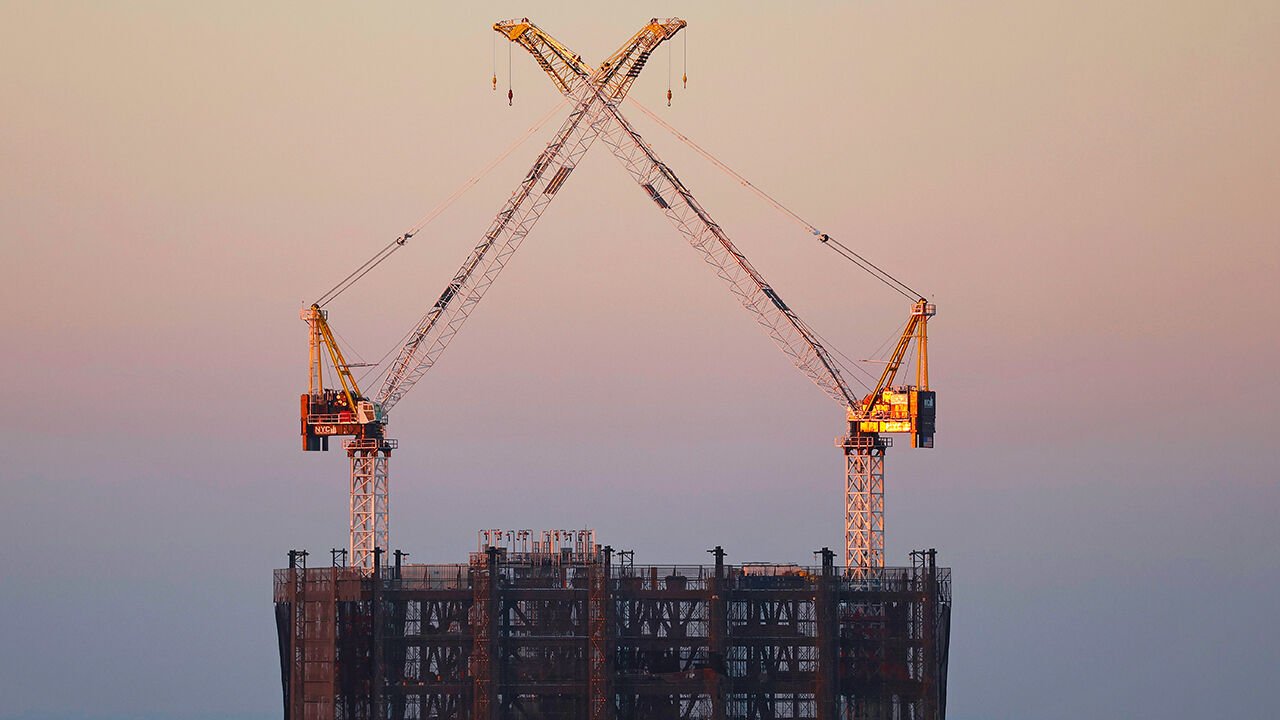

Not lifting a finger

THE EMPIRE STATE BUILDING, finished in 1931, was erected in just 410 days. That same year construction began on the Hoover Dam. It was meant to take seven years, but was built in five. Such feats now seem hard to imagine. Last year half of America’s construction firms reported that commercial projects they were working on had been delayed or abandoned. In 2008 Californian voters approved a high-speed-rail line connecting Los Angeles to San Francisco, to be finished by 2020. It will be at least a decade late.

America’s inability to build is a problem for Donald Trump. Although he has again delayed levying “reciprocal” tariffs until August 1st, the president’s commitment to reviving American manufacturing through protectionism is as strong as ever. But can the country build the factories, warehouses and bridges needed to reindustrialise, and do so quickly enough? And if the administration is to achieve its ambition to win the artificial-intelligence race, it will have to ramp up the construction of data centres and electrical infrastructure, too.

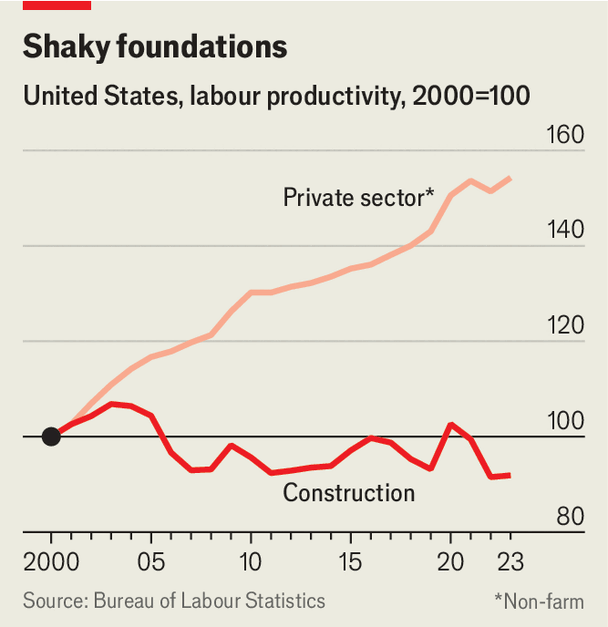

Demand for projects is certainly soaring. Turner Construction Company, America’s largest commercial builder, reported that its order backlog rose by a fifth, year on year, in the first quarter of 2025. Yet delays and cost overruns remain inevitable. Productivity has gone from bad to worse. Since 2000, output per worker in the construction industry has fallen by 8%, even as it has risen by 54% for the private sector as a whole (see chart). The trouble is not limited to commercial projects. America’s house-building companies construct the same number of dwellings per employee as they did nine decades ago, contributing to widespread shortages and soaring prices. Behind this dismal state of affairs is a combination of fragmentation, overregulation and underinvestment.

Start with fragmentation. By one count, there are around 750,000 companies operating in America’s construction industry, roughly three times as many as in manufacturing, which accounts for twice the share of GDP. The result is forgone economies of scale. According to a study by Leonardo D’Amico of Harvard University and co-authors, construction firms with more than 500 employees are around twice as productive as those with between 100 and 499, and four times as productive as those with fewer than 20 workers.

The industry is also characterised by a lack of vertical integration. Giants such as Turner or Bechtel will take on responsibility for big commercial projects but contract out much of the building work to smaller local firms, some of which also sub-contract parts of the job. Housebuilding follows a similar model. That leads to layers of co-ordination, negotiation and payment, all of which can slow down projects. The business of distributing building products is fragmented, too, with inadequate inventories adding to delays.

Why, then, has the industry not consolidated? Part of the answer lies in the thicket of building regulations that has grown steadily denser since the 1970s. These have not only gummed up projects, they have also made it essential for firms to develop detailed knowledge of building codes, which vary from state to state and even across towns. Often the easiest path for national giants has been to enlist local contractors to help complete projects. Such contractors may also be better placed to recruit workers, another challenge in an industry long beset by labour shortages.

This has, in turn, contributed to endemic underinvestment. The legions of sub-scale contractors, which typically operate with razor-thin profit margins, lack the wherewithal to invest in labour-saving technologies, particularly in an industry with such volatile demand. According to Jan Mischke of McKinsey, a consultancy, capital expenditure by the average American construction firm comes to about 3% of revenue, compared with 13% across other industries.

The adoption of new technologies has been lacklustre as a result. The patchy uptake of software tools to plan and manage jobs does not bode well for the industry’s embrace of artificial intelligence. Builders have also been slow to make use of the robots that are increasingly found in factories. There are only six of these for every 100,000 workers in America’s construction industry, according to ING, a bank, compared with almost 3,000 in manufacturing (which is still far below its potential). Of course, the variation in building projects means they cannot be automated in the way factory production can. Even so, robots are able to perform plenty of the tasks, such as laying bricks, welding or moving materials, that take up a significant share of construction workers’ time.

What could pull the industry out of its rut? Mr Trump has promised to hack away at federal rules that stymie construction. On July 1st the Occupational Safety and Health Administration proposed easing rules on things such as the required amount of illumination on building sites, which should help. Yet the president also wants to deport workers who entered America illegally, which would worsen labour shortages, and has slapped tariffs on materials such as steel, which will make projects more expensive.

There are some signs that the industry is starting to consolidate, spurred on at last, perhaps, by meagre profits. Deloitte, another consultancy, notes that there has been an uptick in dealmaking of late. In January Flatiron and Dragados, two big builders, finalised a tie-up. Private-equity firms have been busily buying up and merging smaller specialty contractors.

There has been consolidation in the supply chain, too. In April QXO, a distributor, acquired Beacon Roofing Supply, another builders’ merchant, for $11bn. It now holds a fifth of the market for roofing materials in America. Last month QXO’s bid to acquire GMS, another stockist, was pipped by a $5.5bn offer from Home Depot, a DIY chain that has expanded into supplying contractors. Brad Jacobs, QXO’s boss, argues that digitising the supply chain and improving the flow of materials to builders, as he hopes to do, would help productivity. “There’s a real crisis here,” he says. Digging the construction industry out of its hole will be the mother of all projects. ■