America is coming after Chinese it accuses of hacking

Balancing the books

Can provincial DOGE-ing help them avoid it?

Jul 10, 2025 03:13 PM | BEIJING

UGLY NUMBERS lurk in the books of China’s local governments. An annual audit released on June 24th showed that over 40bn yuan ($6bn) of state pension funds were misappropriated last year in 13 of 25 provinces looked at. (There may be more dodgy practices but the auditors only have the resources to focus on certain bits of the country each year.) Among other things, the money was used to repay government debts. Another 4bn yuan was lifted from a programme to pay for refurbishing schools. And billions more were diverted away from farming subsidies. Local officials “are always stealing our money”, said one angry commenter on Weibo, a social-media platform. “It’s like trusting the mice to look after our rice,” wrote another.

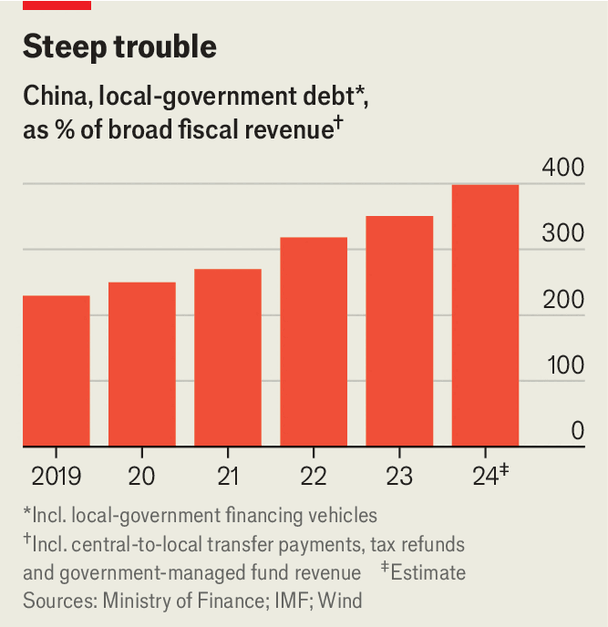

In truth, local officials are motivated more by desperation than greed. Across provinces, counties and cities, they are responsible for the bulk of government spending. But much of China’s tax revenue flows instead to the central government. Local officials used to be able to raise more funds by selling land to developers. But a property slump since 2021 has slashed that source of revenue. Past splurges on infrastructure, meanwhile, have left many governments with huge “hidden” debts, usually within semi-commercial firms known as local-government financing vehicles (see chart). The IMF estimates that such firms sit on 66trn yuan of debt, equivalent to about half China’s annual GDP.

China’s central government has little sympathy for what it regards as fiscal irresponsibility. It hopes that with better budgeting local governments can manage to cut waste at all levels (and so avoid dipping into the pension pot in order to make ends meet). That is why central authorities have been trying harder since 2024 to expand a reform known as “zero-based budgeting”. This requires officials to justify each item in their sprawling budgets (ie, to start from zero) every year. That is in contrast to the current approach, where spending is typically carried forward from a baseline that is set the year before.

In theory, zero-based budgeting should help clear up all sorts of problems. It might prevent companies from being subsidised by multiple agencies at once—a common result of splashy industrial policies—as duplicated spending would be more obvious. It could also help eliminate so-called zombie policies, which continue to be funded after the need for them has passed. And it should make it harder to swipe from government coffers without being noticed.

Pilot schemes have shown some promising results. In Zhengzhou, a city in central China, officials said they recovered 3bn yuan after implementing zero-based budgeting. In the southern region of Guangxi, officials said they found 18bn yuan of idle funds. In March Deqing, a county in Zhejiang on China’s eastern coast, claimed it had slashed its budget for government projects in half by ditching certain projects and merging others. Officials in one department realised that a propaganda campaign to praise the government’s agricultural policies duplicated another’s. They combined the two (no doubt to the relief of local farmers).

In Anhui province, in China’s east, bean-counters claim to have saved 21.6bn yuan since 2022 by nixing hundreds of projects. Before zero-based budgeting, different departments often implemented schemes without even trying to co-ordinate, admitted Zuo Zizhi, an official in Anhui’s finance department, in a report by state television last year. “The transport department might build roads in the west, the water department might dig canals in the east…then the housing department might build cities in the north...they all say that their tasks have been completed, but when you look at the reality, there is no result.” Mr Zuo and his colleagues were also “stunned” to find eight overlapping schemes all trying to fund innovation, according to the report.

Cutting government spending across the board will be significantly harder—just look at the travails of the Department of Government Efficiency in America. So all this might sound rather too good to be true. Still, there is little doubt that China’s local governments could be less wasteful. In March, during his annual report to the country’s rubber-stamp parliament, the prime minister, Li Qiang, promised to support officials in their efforts to take zero-based budgeting nationwide.

The process could prove painful. Yang Zhiyong of the Chinese Academy of Fiscal Sciences, a think-tank under the finance ministry, has said it will require “turning the knife inward” and “biting the hard bones”. So it is not surprising that, whereas almost every province has promised to review its spending, so far only a handful have set proper plans for doing so all the way down to the county level. Those that have, like Zhejiang, tend to be the ones with relatively healthy books already. Guizhou, a south-western province with fiscal woes so serious that staffers in the central government jokingly refer to it as “Greece”, is a laggard.

Given the scale of local governments’ difficulties, the central government may have to help out more at some point. In November, the finance ministry allowed them to issue extra bonds worth trillions of yuan to replace their riskier hidden debts. But so far China’s central authorities have been rather reluctant to offer further support, for fear of encouraging more irresponsible borrowing. In the long run, reforms are under way to shift tax revenues from the central government towards local ones, although the process is expected to take years. Until then, officials must budget better to balance the books. ■