A CEO’s summer guide to protecting profits

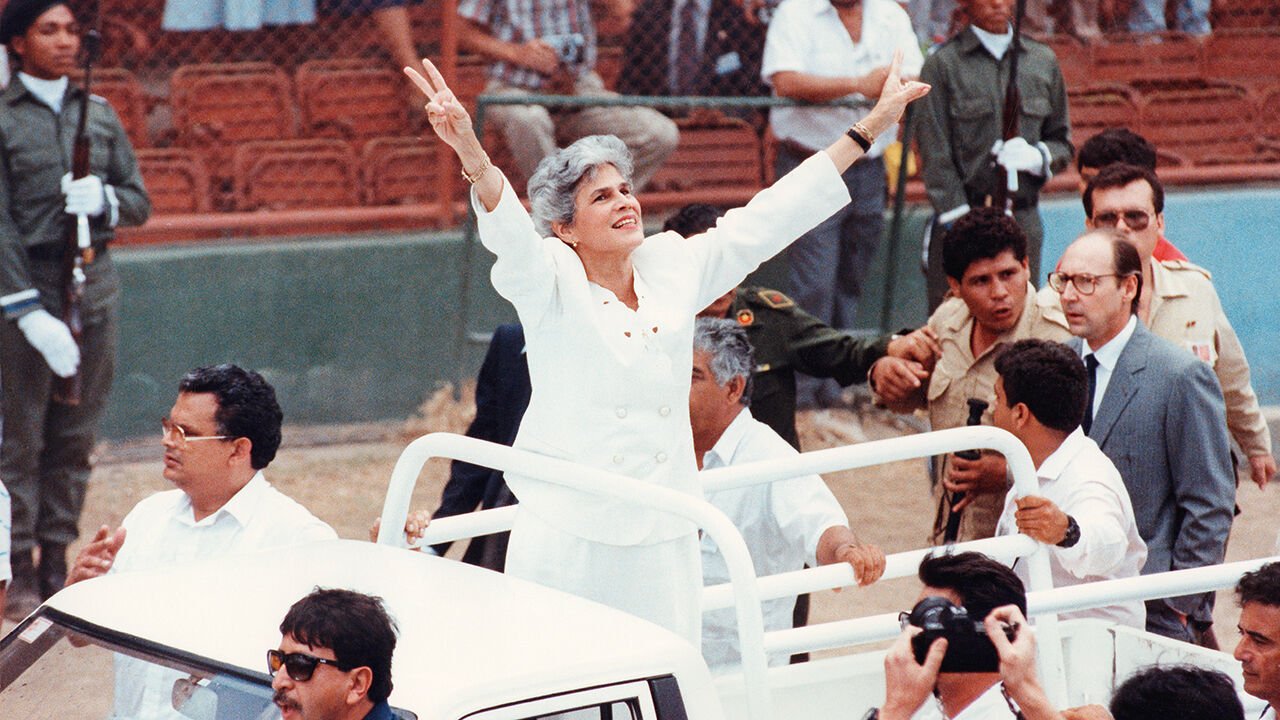

The woman in white

The first female president of Nicaragua died on June 14th, aged 95

Jun 27, 2025 12:57 PM

HER LIVING room was full of dark wood furniture, like a shrine. And that was what Violeta Chamorro intended. The walls were covered with photographs of her husband, Pedro Joaquín: alone, with the family, at work. A glass cabinet held one of his shirts; it was caked with blood. On display too, and bloodied too, were his glasses, the coins from his trouser pocket and the floor-mat from his car. The car itself, restored from the attack, was propped on blocks outside. It was a blood-red Saab.

They had been married for 27 years before, on January 10th 1978, he was shot dead. The order was presumably given by “Tachito” Somoza, the third in the line of dictators who had ruled Nicaragua since the late 1930s. As editor of La Prensa, the Chamorro family’s highly respected newspaper, Pedro had ceaselessly attacked them. He was nothing if not persistent. He had kept chasing her even when she insisted she didn’t like him, or his city ways (she being the daughter of a rancher). She refused to go to the beach with him, but reluctantly one day went with him to mass. He carved a heart into the pew. And it was entirely because of him that she became the first female president of Nicaragua.

She never had the least desire to go into politics, until he died. In macho Nicaragua a girl like her, educated at posh Catholic boarding schools (including in Texas and Virginia) did not need to bother her head about men’s business. Her future when she married was to support her man and bring up children. And that was all Violeta wanted. Being married to Pedro also meant enduring long spells when he was jailed, tortured or exiled for his scathing editorials, but she learned to cope with that. When in the 1970s people began to discuss the Sandinista rebels, who were gathering to oust the Somoza regime, she assumed they were just another band of grumpy young socialists. Pedro was unimpressed for a grimmer reason: they were too Marxist. La Prensa was not much kinder to them than it was to the somocistas.

This meant that when, a year after his death, the Sandinistas swept into power, they were not her friends. At the start she joined the junta, a demure middle-class woman flanked by four scruffy men, but after nine months she said she was ill, and left. It was not quite a lie, because their Cuban-flavoured militarism made her sick. She would not be called “comrade”. They also suggested, at one point, that she should help with the coffee harvest. What, her pick coffee? There were workers to do that kind of thing!

Besides, having taken over La Prensa now, she would not have her views dictated, as Pedro never would. During this decade, with Sandinistas locked in war with right-wing contra rebels, the paper was closed five times. Each time it sprang up defiant. Both it, and she, became symbols of resistance, though without any s_omocista_ connection; so that when an eventual peace agreement mandated free elections in 1990, and four candidates lined up to oppose Daniel Ortega, the Sandinista president, she was suddenly the best bet: the martyr’s widow. She won 55% of the vote.

So there she was, an elegant, silver-haired housewife, in charge of a devastated country. Not only a decade of war, but decades of despotism before it, had reduced its people to despair. Some 40% of the workforce was unemployed, and inflation was more than 13,000%. Since she did not pretend to know what to do, she handed day-to-day governing to her son-in-law, Antonio Lacayo, who patiently and astutely turned policy towards free markets. That improved things to some degree. She could assist by charming presidents in Washington to restore American aid. But her principal task as president of Nicaragua was to be Pedro; to bring about his dream of democracy, reconciliation and peace.

She did so with a mother’s common sense. To her, rebels of any stripe were just boys; she would make them sit down and talk to Doña Violeta about what they really wanted out of life. Before a meeting with Salvadorean guerrillas she kindly sewed on a button for one of them. The contras, whose cause had been backed illegally by the United States, she also called mis muchachos, and persuaded them to disarm in exchange for houses and land. Automatic rifles from both sides were buried under concrete; conscription was scrapped, which reduced the army by more than half. Controversially, because she thought it would avert future violence, she left Sandinistas in charge of the army and police. She also freed from jail the men who had mown Pedro down.

Many people (mostly men) thought she was not up to the job. She strongly objected. She was Violeta Barrios de Chamorro; her family had already produced two presidents of Nicaragua; nobody governed her, and she made the first decision and the last. She had campaigned in white, and wore it later, for a reason: to show she was politically pure, and was dedicating herself to bringing Nicaragua, her family, lovingly together.

That task began at home. Two of her four children, Pedro junior and Cristiana, strongly supported the contras; the other two, Carlos and Claudia, were active Sandinistas (Carlos even running the official Sandinista paper, Barricada). She made sure they came to dinner with her most Sundays, leaving their politics outside. But she did not try to change their minds. At the end of her term she handed power graciously to Arnoldo Alemán, only the second time in Nicaragua’s history that one elected president had succeeded another. In 2007, however, Mr Ortega and his gang of thugs returned to power. Pedro junior and Cristiana were expelled and in 2023 she too, now very frail, left for Costa Rica.

She was still the most popular public figure in Nicaragua. But she had not achieved anything on her own. Besides God, who illuminated her, and Antonio Lacayo, her mainstay, there was Pedro. Persistent as ever, he had advised her all through. Her photos of him and his bloodied relics gave her strength. After she stepped down, she placed among them her framed presidential sash. ■