A CEO’s summer guide to protecting profits

Ice cream: good or bad?

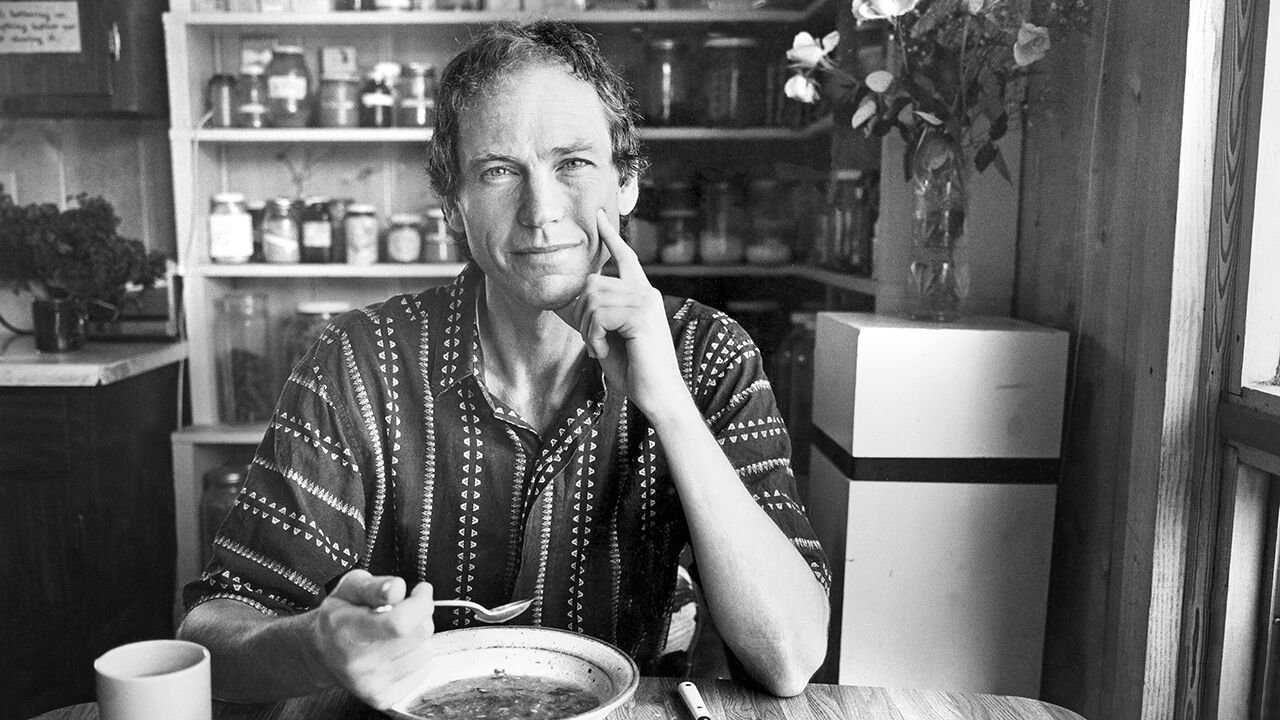

The campaigner for healthier living who spurned a fortune died on June 11th, aged 77

Jul 03, 2025 02:10 PM

WHAT COULD be nicer, as the mercury climbs, than eating ice cream? First, the anticipation, weighing up pistachio versus hazelnut, or praline beside salted caramel, assessing the gooiness or chunkiness of each, before the pleasingly heavy cone is put into your hand. Then that first freezing, caressing tongue-feel, the plunge of the lips into a pure indulgence of creaminess, chocolate swirls, soft biscuit pieces and whatever else you asked for, cooling and satisfying all at once.

This was the fever-dream John Robbins grew up in. His father Irv had set up an ice-cream business in 1945, in partnership with his brother-in-law Burt Baskin. The Baskin-Robbins selling-point was fun. They offered 31 flavours, one for each day of the month. Pink and brown polka dots danced over the stores. There were clowns, and little pink tasting-spoons for customers to dare to depart from their usual vanilla, chocolate or strawberry. Irv himself fooled around for the camera, brandishing a three-scoop cone or tucking into a six-scoop tub. Flavours were named after Beatlemania (Beatle Nut), James Bond (0031) and the moon landing (Lunar Cheesecake). In the Robbins house in North Hollywood ice cream was served at breakfast as well as lunch and dinner. Like all the family, young John ate a seriously excessive amount of it. And as the only son, the company was all his—if he wanted it.

But he didn’t want it, and at 21 he abandoned it. He became famous for promoting a very different kind of happiness: simple living, vegan eating, respect for Earth and compassion for the animal victims of inhumane food production. He preached oneness with, and care for, all creation, starting with ethical meals. His first book, “Diet for a New America” (1987), was dense with charts and tables of the shocking levels of fat Americans ate, the cholesterol that clogged their arteries and the death rates that followed. Ice cream was right there among the baddies, loaded with sugar and saturated fat. The book caused a stir across the country; though not in one mansion in North Hollywood with an ice-cream-cone-shaped swimming pool outside, where the autographed copy he sent to Irv remained resolutely unread.

His father’s expectations had increasingly weighed him down. All through his boyhood he had enjoyed the business of ice cream, even inventing Jamoca Almond Fudge (coffee ice cream with a chocolate fudge ribbon and toasted almonds, 260 calories, 18% fat, of which saturates 50%) all by himself. But unlike his worryingly overweight Uncle Burt, felled by a heart attack at 54, he did not want ice cream to become a fixation. And unlike his father he had no wish to parade in a tuxedo at whites-only country clubs, or own a yacht called The 32nd Flavour. Wealth left him cold. The momentary pleasure of ice cream, that instant gratification, paled beside the sweeter and deeper joy of saving the planet.

So after graduation he fled away with his wife Deo to Salt Spring Island off British Columbia, where he built a one-room cabin. There, part-imitating Henry David Thoreau, he grew as much food as he could, taught yoga and lived for a decade on $500 a year. When he returned to California, to become a psychotherapist and write his books, he still lived with the utmost frugality in a dowdy 1950s house. His vegetable diet, combined with vigorous exercise, made him lean, strong and athletic: no mean feat, when polio had crippled his lower body as a child. He became an ideal advocate for healthy living. Where once he had posed with mouth poised to devour an improbably large vanilla cone, he now embraced the leafiest cabbage he could find.

His uncle’s death had shocked him. Even more, however, he was shocked by his father’s furious denial that ice cream might have been in part to blame. He spent his life correcting that taboo. It was not a matter of simply proving that meat and dairy could be dangerous; he had to prove that vegetables, grains and pulses could provide between them all the protein and iron Americans required. They did not need to drink milk every day, or feast on ground-up cows and stressed-out chickens, to live healthily and well. They did not need to eat ice cream at all.

Such views ran expressly counter to the Great American Food Machine he had once been heir to. He was up against the ruthless lobbying of the meat and dairy industries, which insisted that both meat and milk came from happy cattle. He knew well, from the commercial dairies he had seen, that these were not green pastures but dirt lots; that the cows, permanently pregnant, were treated as four-legged milk pumps; and that their calves were removed at birth for milk-white veal. This became another cause, as did his belief that grazing was reducing America’s forests. The non-profits he founded, EarthSave and the Food Revolution Network, were stretched thin. Luckily his son Ocean had not inherited his anti-paternal gene, but energetically took his missions on.

As those grew, so too did Baskin-Robbins, soon becoming (as it remains) the biggest ice-cream company in the world. Although it kept the “31” logo, its flavours (now including vegan) ran into the hundreds. His father no longer controlled it, having sold it in 1967 to United Fruit. But there was no denting the appetite of humans for ice cream. Even the non-prodigal son himself confessed he had a vegan one occasionally. The flavour he liked best (carefully concocted from almond butter and coconut milk) was the one that came closest to Jamoca Almond Fudge, his and his father’s pride.

He and Irv had not spoken for years. By his 70s Irv was seriously ill with type-2 diabetes and heart disease, as his son could have predicted. One day his cardiologist, in lieu of yet more treatment, handed him a book. It was “Diet For a New America”. His father opened it at last, read it, began to improve, and two years later called to say “It turns out you were right.” As joys went, this was not on the level of enlightening the whole country. But it was worth quite a number of Rocky Roads. ■