A YouTuber kicks up a stink over a flatulent “reaction” video

Fatal attraction

Why fluffy, glossy K-dramas tempt North Koreans to brave the firing squad

Jul 03, 2025 02:10 PM | SEOUL

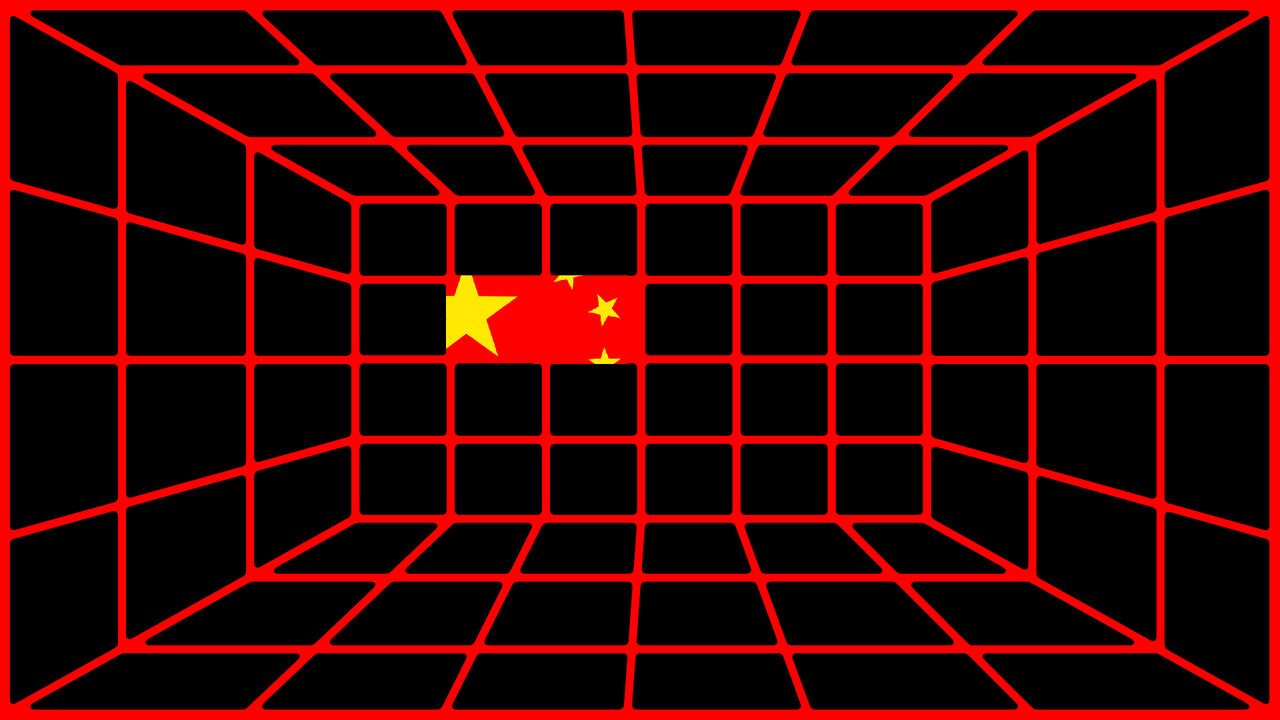

IN MOST COUNTRIES, good television is cheap. A monthly Netflix subscription costs less than a takeaway pizza. In North Korea, by contrast, watching a gripping TV drama can cost you your life.

Under the “Anti-Reactionary Thought Law” of 2020, no North Korean may consume, possess or distribute the “rotten ideology and culture of hostile forces”. That means K-dramas and K-pop, as well as South Korean books, drawings and photographs. The penalties range from forced labour to prison camp to death. Human-rights groups report multiple executions. In 2022 a 22-year-old farmer was executed for listening to 70 South Korean songs and watching three South Korean films, which he shared with his friends.

Yet despite the danger, North Koreans avidly tune in to K-dramas. A survey of defectors in 2016-20 by South Korea’s unification ministry found that 83% had watched such shows before defecting. The rate among other North Koreans may not be as high. But Kang Gyu-ri, who defected in 2023, says of her millennial peers in the north: “They might not say it [publicly], but I didn’t know anyone who hadn’t watched a foreign video.”

What kind of TV shows are worth the risk of death? To answer this question, consider the clunky, earnest fare that North Koreans are supposed to watch. In “A Flower in the Snow” (2011), a North Korean movie, the female lead polishes her fiancé’s shoe at a train station—right before she breaks up with him to commit herself to reviving an old blanket factory and raising orphans. Ultimately, she succeeds in restarting the factory; her ex-fiancé tragically dies while delivering equipment to it.

South Korean dramas offer a less totalitarian take on romance. Ryu Hee-jin, a former swimmer from Pyongyang, has explained the difference: “In [South] Korean dramas, you can see people saying ‘I love you’ so freely. In North Korea, you could only say that you love Chairman Kim Jong Un and his father.”

Ms Kang’s favourite K-drama was “May Queen” (2012). She first watched the melodrama on a smuggled SD card in the middle of the night—and re-watched it 20 times. Over the course of almost 40 episodes, a plucky protagonist, Chun Hae-joo, overcomes poverty and family intrigue to become a ship designer. She eventually meets the love of her life and, rather than ditching him to work at a grotty state-owned blanket factory, takes her rightful place as the head of the family business and escapes her shadowy past.

“Watching it gave me strength,” recalls Ms Kang. She, too, worked in the ship business and had to overcome adversity, dealing with corrupt officials and disrespectful customers twice her age. “[Chun] was a role model to me, the way she kept holding on and pushing through truly difficult circumstances at a young age,” she says. “I felt like that was me.”

For North Koreans, “Media isn’t just entertainment, it’s information,” says Lee Kwang-baek of Unification Media Group, an NGO that produces content specifically designed to be smuggled into the north. A seemingly shallow show can offer a window into otherwise inaccessible worlds, he argues. North Korean propaganda once claimed that the south was an impoverished, crime-ridden hellscape. South Korean dramas—with background shots of streets full of cars, meaty meals and luxurious apartments—offer a rebuttal. Ms Kang remembers how even mundane elements revealed how much more freely South Koreans live, such as the diversity of hairstyles. She can’t remember the male lead’s name in “Boys Over Flowers” (2009), a pan-Asian hit, but she remembers his distinctive “pineapple” cut.

Both South Koreans (legally) and North Koreans (illegally) fell head over heels for “Crash Landing on You” (2019), a fish-out-of-water romance. A South Korean heiress finds herself stuck in the north after a tornado catches her paraglider and blows her over the border. A handsome northern soldier finds her while on patrol and agrees to help her get back home. As well as squeal-inducing romance, the show offers fairly accurate depictions of life in both Koreas, giving audiences on both sides of the 38th parallel some valuable perspective.

For North Koreans, South Korean dramas are both familiar and exotic. The actors look and sound Korean, obviously, but big budgets and whizzy special effects make them seem far more glamorous than their North Korean counterparts. Fans tacitly emulate them. Enterprising barbers in North Korea have learned to mimic southern hairstyles; young people often imitate the South Korean way of speaking. To crush such filthy capitalist subversion, the government passed another law in 2023, the “Pyongyang Cultural Language Protection Act”, which bans women from referring to their boyfriends or husbands as oppa (literally: “older brother”, a common form of address in South Korea).

North Koreans go to great lengths to watch their favourite shows. Some live close enough to the border to jailbreak their televisions and pick up broadcasts from China or South Korea. (Ms Kang did this.) Others watch shows smuggled in from China on flash drives or SD cards. Some borrow the memory cards from friends. The lucky few with money buy them on the black market.

Though the K-dramas popular in North Korea are largely apolitical, the regime sees them as a growing threat—hence the harsher punishments. In the past, the death penalty was reserved for distributors of film and TV. Now it can be imposed for mere possession.

Kim Jong Un, the north’s hereditary despot, is correct that fluffy K-dramas undermine loyalty to his joyless regime. North Koreans are constantly told that they live in a people’s paradise thanks to the godlike leadership of the Kim family. Depictions of the vastly better lives of their southern cousins remind them that they do not. That is why the regime not only surrounds the country with razor wire to keep people in, but also sends the relatives of defectors to labour camps.

Ms Kang says that glimpses of the south on screen helped inspire her to defect. She and her family crammed into a small fishing boat and evaded coastguards before being rescued by a fisherman in South Korean waters. It was a daring escape worthy of “May Queen”. ■