A new Dutch museum tackles migration through art

Pitt stop

Will it rev up new fans for the motorsport?

Jun 27, 2025 12:08 PM | NEW YORK

HOLLYWOOD HAS not always been kind to the world’s most popular motorsport. In “Talladega Nights” (2006), a dimwit comedy, Formula One (F1) was personified by a French driver who brags that his countrymen “invented democracy, existentialisme and the blowjob”. F1, in this telling, was pretentious and it was foreign: an interloper in NASCAR-loving America.

No longer. “F1 The Movie”, released in cinemas this week, reflects how the sport has accelerated in ambition and scale in the past two decades. It is reportedly one of the most expensive films ever made (with a reputed budget of more than $300m). One of the producers is Jerry Bruckheimer, who, in “Black Hawk Down” and “Top Gun”, brought thrillers involving choppers and fighter jets to screens. And, crucially, its protagonist is not a pompous European but a hunky American, played by one of the country’s most bankable heart-throbs, Brad Pitt (pictured).

The plot of “F1 The Movie” is made up—Mr Pitt plays a retired driver who decides he has more fuel in the tank—but it strives for verisimilitude. The movie was made in collaboration with F1. To understand how to get viewers’ pulses racing, the film crew attended fixtures and Mr Pitt learned to drive at 300 kilometres an hour. Lewis Hamilton, a driver who is also a producer of the film, makes a cameo.

F1 has done a better job of marketing itself on film and television than any other sport. “Drive to Survive”, which goes behind the scenes and behind the wheel at the World Championships, has won the sport legions of fans globally. According to Parrot Analytics, a data firm, the docuseries brought in $290m in revenue for Netflix in 2020-24. (Other sports have since tried to copy the format, with mixed results.) In May Netflix released “F1: The Academy”, which focuses on woman drivers, to cater to the sport’s growing female fanbase.

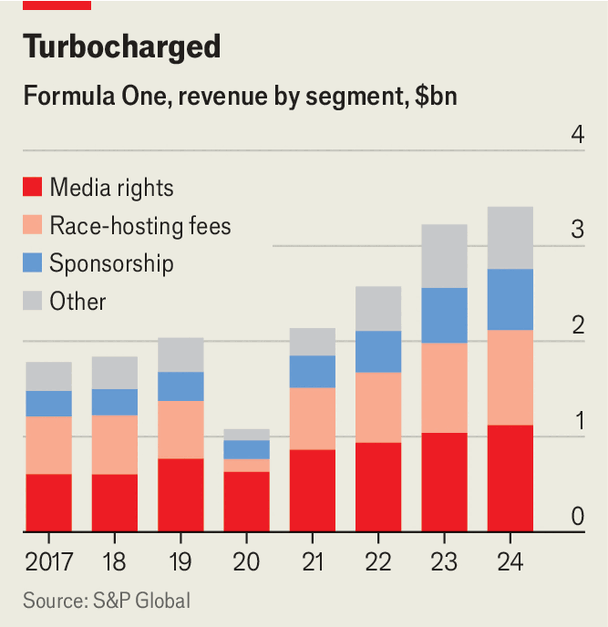

In some ways, this is surprising, as the sport itself can be tedious. For many, watching cars noisily circle a track for two hours is duller than wiping a dipstick. Yet when Liberty Media acquired F1 in 2017, the firm shifted gears. It booted out Bernie Ecclestone—who had professionalised the operation but was later convicted of tax fraud—and introduced a new way of thinking. The late Teddy Mayer, former head of McLaren, a British team, had once likened drivers to lightbulbs: screw them in and the vehicle does everything else. Liberty saw drivers as electric in their own right.

Derek Chang, Liberty’s boss, has described F1 not as a sport but as a “content producer”. The league introduced F1 TV Pro, a streaming service offering bonus coverage, and a suite of podcasts. It produced videos on social media for the sorts of fans who, according to Mr Chang, do not care about braking stability yet do care “what drivers are eating for breakfast, what they’re eating for dinner”.

It is telling that Ian Holmes, F1’s chief media-rights officer, refers to the league’s 20 drivers as its “cast”. The drivers travel to glitzy locales on five continents and spray magnums of Moët on the podium. Add some interpersonal squabbles and you have the makings of a reality-TV show.

Indeed “Drive to Survive”, now in its seventh season, has proved to be addictive TV. James Vowles, who leads Williams, one of ten teams in the championship, calls the show “transformative”. Viewers are introduced not only to the drivers, but to the engineers, mechanics and corporate sponsors who power each car. Some think the show is simplistic and even deceptive. Pierre Gasly, a driver, has said that the drama was “kind of made up”.

Maybe so, but the format has sent adrenaline and ratings soaring. According to Nielsen, a research firm, in 2022 some 360,000 Americans started tuning in to Grands Prix after watching “Drive to Survive”. The show captures the high stakes of the sport: a mistake on the track, unlike on a court or a pitch, can lead to fatalities. (That is emphasised in “F1 The Movie”: Mr Pitt’s character was initially forced to retire after suffering a terrible crash.)

Liberty wants more growth in America, hence the Hollywood treatment. Alongside Austin, it has added Grands Prix in Las Vegas and Miami; next year Cadillac, an American team, will join the grid. Average race viewership on ESPN has more than doubled since 2018, to 1.3m, raising the price of its broadcast rights in America from $5m a year in 2019-22 to a reported asking price of between $150m and $180m.

Nonetheless, F1 is some way off catching up with NASCAR, not to mention American football and basketball. Mark Gallagher, who worked in the sport for decades, reckons F1 needs a homegrown superstar—a Mario Andretti for the 21st century—if it is to truly gain pace in the country. F1, in other words, should try to make its own movie a reality. ■